In today’s Substack, I’m going to ask us to consider making a big change in the way we look at, and how we draw conclusions about, events in our lives. I would like us all to consider thinking differently to make what we see as our biggest problems far more moderate and manageable.

I think we all know we carry these ongoing, unspoken but powerful and repetitive scripts in our minds, most of them negative in nature. Many of them catastrophic:

“I’m never gonna get over this breakup.”

“I’m just always going to be unhappy with my body.”

“They told me no. I’ll never get a job.”

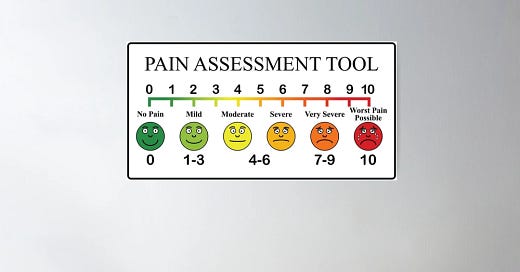

“This pain is terrible, ten out of ten, and I’ll never get past it.”

“This is the worst thing that could happen to me.”

We humans have this bizarre habit of taking fairly ordinary situations and making them feel an awful lot like catastrophes. In doing so, we summarily remove any agency we might have to exert over the issue, rendering us helpless victims to our seemingly tragic circumstances. I’ll ask you to pause here and think about this for a moment, and how it may apply to your own life. What issue or event do you make catastrophic, just in the way you look at it? Is it truly awful? Do you really have no agency or control over the situation?

Or are you catastrophizing?

When I talk to groups of parents, I often start by asking them how many crises they’ve suffered in their lives? I start by requesting a show of hands: “How many of you have suffered more than ten crises in your lifetime?” Typically, more than half the hands in the audience rise. No real surprise there. Many of us have lost loved ones and jobs. We’ve suffered accidents, family strife and devastating diagnoses. Some of these issues can rise to the label of crisis, even catastrophe.

Then, I recalibrate the term crisis, suggesting we use death, a lethal diagnosis, or even 9/11 as our benchmark crises. I then ask the exact same question again: “Now how many of you have suffered more than ten crises in your lifetime?”

And virtually nobody raises their hands.

It’s that recalibration I’m going to ask you to consider implementing today. If we can shift our thinking about crisis and catastrophe, if our 8 out of 10 can be downgraded to a 1 or 2, then I think we’re headed in the right direction. Yes, the change I’m requesting is neither temporary nor granular, but big, broad, and permanent, a raised plateau. Let me explain why this is so important.

Why we do this

So many of the people I work with arrive in the therapy room deeply concerned about their own personal feelings of depression, despair or hopelessness. Some show up here after suffering decades of symptoms, only seeking help as their level of functioning grinds to a standstill, something like, “Duffy, I just can’t get out of my head and get perspective on anything that’s happening. Everything just feels awful, and every little element of my life is affected negatively.”

Magnifying difficulties to the point of catastrophe is honestly among the most common problems I deal with at work day-to-day. But for a lot of us, it’s difficult to gain perspective on the why, or even recognize that’s what we’re doing, that our own thinking makes us feel this way. Instead, we ask ourselves questions: Why do awful things continuously happen to me? How can other people pass through their days in a state of bliss, or at least not a deep state of existential dread? Are they not experiencing the same life as me? Or am I looking at my life all backwards and wrong?

These are the right questions, but answers don’t always come easily.

In the end, I find we catastrophize, at least in part, to buffer the impact of future negative events. We may have been through something exceptionally traumatic or difficult early in our lives and felt shocked and ill-prepared. So, we shift our future thinking into doomsday mode. We’ve learned from experience, after all. Now, we figure, we can prepare for the worst, brace ourselves against future threats to our well-being.

Impact on ourselves

I’m pretty familiar with this phenomenon myself. In my most anxious days, I would practice this maladaptive thinking quite a bit. My family was rigid, uptight and emotionally non-expressive throughout my youth. Nothing terrible happened necessarily, but it often felt terrible in my home and, eventually, in my own mind. In retrospect, each of us Duffy kids responded with some form of anxiety, and it presented differently in each of us. For some of us, it ended up far more lethal than for others.

For me, the symptom profile included panic and dread. I was scanning my environment for danger nearly constantly. I couldn’t even tell you the nature of the danger I feared. Hell, I just thought I was born with a weaker makeup, and less fortitude, than most people. I thought I was the only one struggling like this. I was stunned to learn, in our singular family therapy session, what a panic attack was. That it had a name. That other people felt like I did.

That was a tad helpful, but not sufficient to neutralize my negative thought patterns. Those persisted and grew stronger well into my adult life. It wasn’t until I sought out my own therapy that I recalibrated my thinking. I took crisis and catastrophe out of my daily internal vernacular, substituting difficulty or, better in most instances, just situation.

Once I was able to break the catastrophizing habit, my panic and anxiety subsided fairly quickly. I’ve collaborated with countless clients to do the same over the years. It’s a crucial component of my therapy practice.

I find we cause ourselves an undue degree of pain, anxiety and depression when we catastrophize situations and circumstances. For many of my clients, tuning down the amplitude of these issues is the primary, sometimes sole goal.

Without some degree of change in perception, we drive up our sense of hopelessness. We feel more depressed. We become increasingly anxious. This toxic emotional environment can literally ruin our lives. The impact is, to say the least, significant.

Impact on our kids

I’ve noticed catastrophic thinking taking hold of more and more kids with each passing year. There may be a number of reasons for this phenomenon. Many of them grew up in the shadow of a global pandemic. Divisive politics have played a significant role in their lives to date. They’re also the first generation that’s been fed bottomless bad news online, fresh wretched headlines most every day, sometimes every hour. It’s not easy to hold a positive worldview under these circumstances, when you’re being told catastrophic events are taking place all the time. Cortisol flows pretty readily. Alarm bells rarely cease, and the mind is hardly ever calm.

As a result of all of this, our kids’ thinking can become distorted as they struggle to determine what conditions make up a true crisis. But I see my young self in a lot of the kids and young adults I work with. Through tortured minds, they work hard to calibrate their thinking about the world, and the triggers and dangers it may bring.

Many kids today become avoidant, discerning that home is the only safe space for them (and for some of them, not even there). So, I see them regress, isolate, and over-protect themselves from the perceived dangers of the world, of school, of judgment, of adulthood.

They also feel precious little agency and control in too many aspects of their lives. They don’t feel strong. They absolutely don’t feel resilient and flexible and adaptable, fully prepared to take on any challenges they may face.

Their bar for crisis is, on the whole, far too low.

As a result, kids today too often tap out of experiences, their internal meters so poorly calibrated that they see a potential threat in virtually every situation. And each symptom of depression, anxiety, attention difficulties, and hopelessness can readily overtake their taxed and exhausted hearts and minds. Again, the impact of catastrophic thinking is quite significant for our kids.

And as with so many issues, they’ll tend to draft off of the way we see the world. So, the good news beneath the alarming headline here is that, by example, we can show our kids a brighter path. By taking crisis vocabulary out of our repertoire, for the most part, and recognizing our own strength and resilience to endure difficult situations and challenges, we are modeling the same for our children.

The recalibration

So, I’m asking you to downgrade catastrophe, to recognize that the difficulty you’re experiencing now is likely more manageable than you think. That your 7 or 8 is actually a 1 or a 2. Also, remember that you are strong and capable, and can manage far more difficulties and challenges than you think, with far more grace and ease than you’d imagine. Remember that in all likelihood, this thing that troubles you today won’t likely matter in six months, or a year, or a decade. Recognizing and accepting this reality is the magic trick, the fix. If we can accomplish this feat, this shift in thinking, we allow space for our minds to function better, to think more clearly, to make far, far better decisions.

This is quite important, as we tend to make poor decisions under stress and distress. And we suffer unnecessarily, sometimes exponentially so. And I should note that catastrophizing tends to become habitual over time. Despite the fact that we suffer it enormously, we also tend to repeat it, perhaps in preparation of future emotional storms as suggested above. But this does our fragile psyches and our nervous systems no favors. And the massive cortisol rush can drive wildly uncomfortable anxiety that, over time, can negatively impact our overall health, no small thing.

The way I see it, there are enough crises and catastrophes and miscarriages of justice taking place on a global, macro level these days, one-upping each other in their awfulness. There’s no need for us to add to the trauma on a micro level. Let’s skip the unnecessary stress and suffering. Let’s allow the little problems in our lives to remain little. Let’s reason with that irrational part of our brains, and free ourselves up mind, body and spirit.